Every battle is won or lost before it’s ever fought.

– Sun Tzu

The impact of metaverses on warfare may be greater than anticipated. Advances with robotics and AI have spurred the idea of having war without people, or at least with reduced risks of human injury (Scharre, 2018; Kallenborn, 2020). What if we could extend this idea, looking towards a time when war could be fought virtually? How far are we from Ender’s Game, whereby we conduct (or simulate) battles before they are ever fought, and thus save lives during potential failures? How much of what we see and hear about a metaverse is just hype (Card, 1985; Chowdhury and Marler, 2024)? In fact, we may be on the path to leveraging metaverses for more than just entertainment or training. It may be that applications and implications are broader and more significant than anticipated. Technologies like hypersonics, AI, biotechnology, and directed energy have captured the headlines with respect to impacting the nature of warfare. Metaverses may deserve these headlines as well. They, too, may have significant implications for securing the future operational environments and advancing the future force.

As with any emerging technology, leveraging the benefits of metaverses requires first understanding what this technology entails. We must define what a metaverse is. In addition, we must consider both benefits and risks concurrently. Among the many emerging technologies that may impact the future of warfare, there may be an unrecognized opportunity with metaverses. To be sure, virtual environments, arguably the crux of metaverses, provide untapped benefits to training (Marler, 2023). But, metaverses may offer broader benefits than realized, and thus, it may be prudent to explore the various opportunities now. This, in turn, can inform key considerations for development and deployment in the context of military applications. Rather than being reactive, setting policies and refining research and development plans after emergence, perhaps we can take steps to plan ahead.

A pervasive and increasingly important aspect of future warfare is Joint All Domain Operations (JADO), and this offers a context for exploring the broad benefits of metaverses. However, as with emerging technologies, operating concepts and doctrine must first be defined with a clear scope before one considers the effects of a particular technology. Thus, after discussing what a metaverse is, we summarize JADO. Then, we pose opportunities derived from metaverses and related key development and deployment considerations that can foster effective use.

... metaverses may offer broader benefits than realized, and thus, it may be prudent to explore the various opportunities now. This, in turn, can inform key considerations for development and deployment in the context of military applications.

Dr. Tim Marler

What Is a Metaverse?

As the result of much publicity and hype, the term metaverse has taken on many different meanings, often obfuscating its practical value. Thus, before discussing its benefits to warfare, it can be helpful to review definitions. Stephenson (1992) provides the first definition of a metaverse as a virtual reality-based successor to the internet, presented as an escape from a dystopian society. Although today’s society is not necessarily dystopic, Stephenson’s novel, Snow Crash, may have been predictive (Robinson, 2017). The concept of a metaverse does indeed extend the concept of the internet. As Marler et al. (2023) explain, there are multiple definitions of metaverse, but they can vary substantially (Smart et al., 2007; Ball, 2021; Park et al., 2022). Companies offer their own differing definitions of metaverse, often slanted to suit their own needs (Meta, n.d.; Roblox, 2021). Microsoft goes so far as to tie their definition to digital twins (of people), which is yet another term with many uncoordinated definitions, but they also note the connection to the physical world (Roach, 2021). In this context, digital twins are essentially digital replications of real entities or environments, and although they are in some sense a subset of metaverses, they can have significant comparable value (Poon, 2022). The term metaverse made public headlines when Facebook announced a name change to Meta (CNET, 2021). Ball (2021) notes that “…we should not expect a single, all-illuminating definition of the ‘Metaverse’…” especially when metaverse-related technology is still emerging.

The etymology of the word metaverse offers some additional insight into a potential consistent definition. The prefix meta can mean the following (Merriam-Webster, n.d.):

- occurring later than or in succession to; after

- change; transformation

- more comprehensive; transcending; beyond

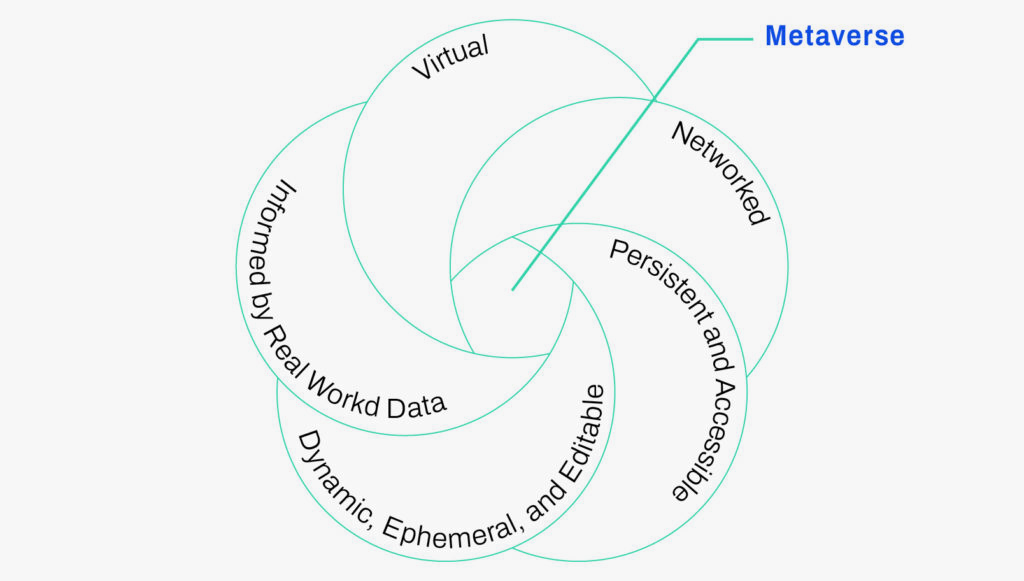

Assuming the term verse is derived in this context from the word universe and is thus well understood, metaverse technically means a new, transformative, and comprehensive universe. While this history provides context, there may still be little consensus on a specific definition (Chowdhury and Marler, 2022). Consequently, Marler et al (2024) present six key characteristics, with discussion of practical implications, as illustrated in Figure 5.1:

1) Virtual; 2) Networked to facilitate interaction between users and instances (of metaverses); 3) Persistent and accessible; 4) Dynamic, ephemeral, and editable; 5) Informed by real-world data; 6) Defined by people involved in its development and use.

Characteristics one through five may be more relevant for JADO military applications. Regardless, when aggregated, these key characteristics suggest a definition of metaverse as a persistent and digital environment, potentially informed by real-world sensors, that someone can enter and assume a persona, interact with others, have affordances and agency, perhaps modify the environment itself, and then leave.

While Marler et al. (2024) provide more extensive discussions, it is worth elaborating on the significance of some of these characteristics that are particularly relevant to warfare and JADO. First, a metaverse is not just a realistic virtual environment; it is more than a video game or scene that a user can traverse. As itemized above, there are multiple key characteristics that extend the metaverse concept beyond what is often implied. Second, with a metaverse, a user can access a virtual environment multiple times and can permanently alter it. For example, one could enter a virtual room, activate a virtual landmine, and then completely logoff of their computer. That virtual landmine would still be present (and possibly functional in a virtual sense) for other users who may enter that same room after the original user had left. Finally, despite the public discourse about the metaverse, there can be multiple virtual environments, possibly multiple distributed, integrated metaverses. The metaverse has become synonymous with the overarching concept, although technically, there may be multiple integrated virtual environments. A user may effectively move from one environment to another, with the environments hosted on different computers and managed by different owners, all within what appears to be a single universe.

What is JADO?

JADO entails “…actions by the joint force in multiple domains integrated in planning and synchronized in execution, at speed and scale needed to gain advantage and accomplish the mission” (Air Force Doctrine Publication 3-99, 2020). It includes the air, land, maritime, cyberspace, and space domains, as well as the electromagnetic spectrum. JADO is based on the underlying concept of multi-domain operations (MDO), but it emphasizes the need for and challenges behind joint coordination.

As Marler (2022) notes, the definition of MDO can vary. Although the fundamental concept is not new, the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command introduced the term in 2018 (TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, 2018). Fundamentally, MDO is an operational strategy, describing how the Army will fight across all domains, including the electromagnetic spectrum and the information environment. Specifically, MDO can be defined as follows (Kasubaski, 2019):

“A campaign, consisting of multiple battles and operations, conducted across domains, time, and contested spaces culminating in the convergence of friendly forces (Joint/Coalition) capabilities that increase limiting factors against an adversary (or enemy) and decrease limiting factors on friendly forces, opening up multiple windows of opportunity to achieve decisive blows against adversary (or enemy) critical vulnerabilities and COGs [centers of gravity].”

JADO emphasizes the interconnectedness of assets, distributed operations, delegated authorities, and integrated planning across all domains (Air Force Doctrine Publication 3-99, 2020). The goal of JADO is to enable the integration of effects across domains, to deter and defeat near-peer adversaries (Air Force Doctrine Note 1-20, 2020). Ideally, distributed sensors, shooters, and data from all domains are connected to joint forces, enabling the coordinated exercise of authority to integrate planning and synchronize convergence in time, space, and purpose (LeMay, 2020). With respect to doctrine, JADO “…is a cross-department variation of the various service cross-domain doctrine, [that] injects battlefield engagements with a convergence of speed and scale effects that can overwhelm an enemy, including near-peer adversaries, and clinch mission success” (BAE Systems, n.d.). Consequently, it requires coordination and cooperation between all stakeholders, including all military Services.

The fundamental nature of JADO points to alignment with key characteristics of the metaverse. First, the “joint” element of JADO necessitates coordination between various Services, and the idea of linking multiple distributed virtual environments may support this. When this idea is extended to include partners and allies, it constitutes combined joint all-domain operations. Second, the “all-domain” element necessitates the ability to simulate an expansive universe, potentially including air, land, maritime, cyberspace, and space. However, metaverses may offer an even broader range of opportunities and benefits for JADO, and these warrant further discussion.

Given eventual substantial improvements in fidelity, connectivity, and accessibility, the military may be able to substantially reduce the need for large-scale multinational training exercises.

Dr. Tim Marler

A New Domain - Benefits of Metaverses

Underestimating the relevance of metaverses for JADO and warfare more generally could be a mistake. Thus, while we do not itemize every benefit here, we will highlight some potential opportunities and applications that may not yet receive the attention they deserve. Subsequently, we touch on risks, challenges, and necessary considerations during development and use.

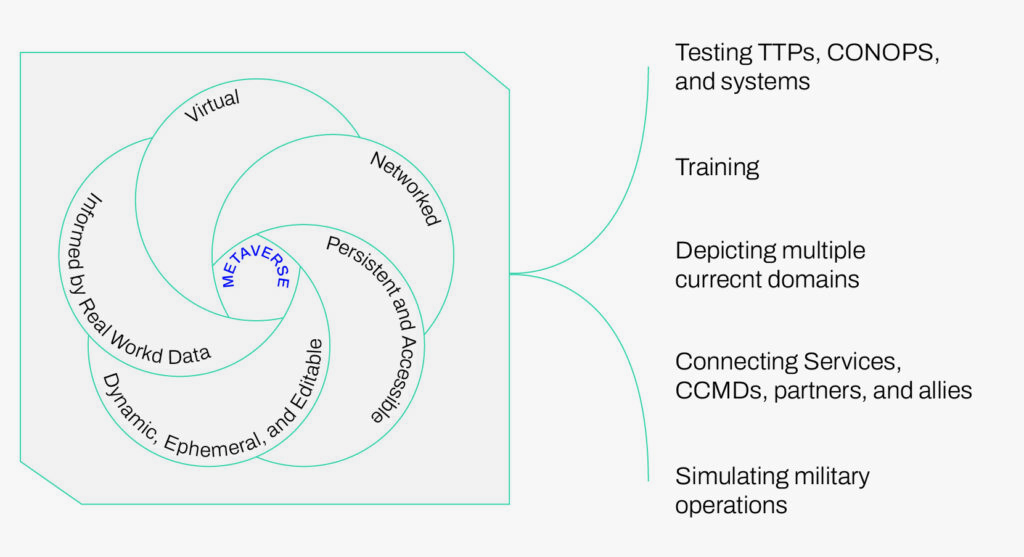

Fundamentally, a metaverse may provide a complete virtual world, whereby anything that is possible in the real world is possible in the metaverse(s), other than biological functions (e.g., eating, exercising physically). Such a world could also come with risks and challenges (e.g., theft, harassment). Of course, metaverses are far from mature; they are still developing. Nonetheless, conceptualizing a metaverse as a complete alternative world and comparing it to the fundamentals of JADO can highlight unsuspected and potential benefits. While metaverses do stand apart from just basic virtual environments, much of the value with respect to JADO derives from potential future scale and fidelity of the virtual environments. Additional specific benefits are noted in Figure 5.2:

A primary benefit might be that a virtual world could allow military users to test equipment and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) in a relatively (physically) safe environment. Concurrently, a virtual world could have many benefits for training, ultimately in highly complex environments that involve multiple domains (Marler, 2022, 2023). Thus, a metaverse could support training enhancements that save lives in real situations. With appropriate advances in all dimensions of fidelity (Straus et al., 2019), a metaverse may help integrate test and training, allowing one to use the same simulation capabilities and scenarios for both. In this context, test applies to strategies, TTPs, and concepts of operations (CONOPS). However, testing actual capabilities and weapons systems in a metaverse could have significant implications for acquisition of new systems or refinement of existing systems, especially as the ability to create and use highly accurate digital twins matures. Metaverses could facilitate more effective testing or systems and procedures within a realistic environment and situation. To be sure, the DoD has invested in simulations and simulators for decades. The idea of a metaverse, however, reflects a more expansive and comprehensive virtual world that could enhance test and training.

Another benefit of metaverses is that with them, it may be relatively easy to depict multiple domains within a virtual environment, and thus, metaverses may help simulate JADO. However, as implied by the characteristics of metaverses, a user would not just view or traverse such domains. They would be able to alter them, presumably as a result of battle. Any changes – beneficial or detrimental – can be permanent, so using metaverses brings a temporal element to today’s virtual environments that tend to be static and reset with each use. This in turn can have implications for decision making when considering longer-term effects.

In addition to representing multiple domains, metaverses will inherently facilitate connectivity, making large-scale training exercises relatively easy as compared to real-world exercises. The interconnectivity of metaverses – various virtual environments – could allow various Services, Combatant Commands, partners, and allies to train and test together seamlessly. In this way, metaverses could facilitate improved coordination and collaboration. Today, various software systems and simulators are indeed connected and networked, but they fall far short of providing a complete “world.” Providing connectivity and integration across the Services supports the Joint aspect of JADO. Metaverses, however, may help provide integration not just across U.S. Services and Combatant Commands but also partners and allies. This could have significant benefits for areas like the Indo-Pacific region, which involves many different partner nations with no single common organization (e.g., NATO). Given the potential breadth of concurrent users, metaverses could also facilitate broad distribution of data and information. It may essentially provide a novel communication system.

To be sure, gaming has provided value in military training for over a decade, demonstrating the benefit of software systems that allow disparate groups and individuals to integrate and train together (Shaban, 2021). Metaverses, however, would extend this capability, allowing the joint force to train and fight across all domains virtually. Given eventual substantial improvements in fidelity, connectivity, and accessibility, the military may be able to substantially reduce the need for large-scale multinational training exercises.

In addition to the advantages of using metaverses for distributed, joint, all-domain, test, training, and communication, perhaps the more exciting use is for actual military operations. A persistent, mutable, virtual environment that replicates the real world could support real-world operations in real-time. For example, metaverses could provide user interfaces for operating the expanding range of unmanned systems. When considering the ability to support distributed users, federated metaverses could also enhance situational awareness, allowing users to view, experience, and evaluate the battlespace at various levels and echelons. In essence, integrated metaverses could provide a comprehensive common operating picture (COP). They could provide the ability to develop, change, and use an infinite number of situations, which could include all domains of warfare (Marler, 2023).

Ultimately, many different individuals, organizations, and states may have agency in metaverses. They may have assets and equity in a virtual world, but with real value. There may be opportunities for new forms of commerce. Consequently, they will be susceptible to incentives and may impose incentives on others. Thus, like present-day “gamers,” who compete in a virtual environment, various states may compete within a metaverse and perhaps even wage certain aspects of warfare. Metaverses could thus facilitate virtual warfare with real consequences, presumably falling short of physical harm. Perhaps metaverses become the next domain, extending from the cyberspace domain. If so, what would it take to make victory in this new domain – this virtual world – so assured, so unquestionable that battle is won before it is ever fought?

Given eventual substantial improvements in fidelity, connectivity, and accessibility, the military may be able to substantially reduce the need for large-scale multinational training exercises.

Dr. Tim Marler

Considerations for Developing and Winning in the New Domain

A keystone in governing this new domain may entail taking leadership in its creation. It is a unique opportunity to build a new battle domain. Now, as virtual environments are viewed primarily as tools for training and entertainment, there is an opportunity to take the lead before the potential impact of metaverses is realized.

Developing metaverses to provide the benefits described above will involve overcoming challenges. These will be both technical and organizational. Taking the lead means first addressing these challenges or at least developing solutions.

One of the key considerations will be content ownership. Who owns what content in a metaverse or federations of metaverses, and who has access and editorial rights? To a large extent, at least initially, whoever builds it, owns it. In as much as metaverses may be extensions of the internet, policy surrounding the internet may provide a starting point, albeit an imperfect one. Related to ownership, cybersecurity will be another key consideration, just as it is for the internet. Here again, policies and best practices for the internet may provide a stepping stone.

Especially with regard to interconnected metaverses (e.g., one for each traditional domain), standards for interoperability will be critical. A federated metaverse will likely require that all users subscribe to a certain set of standards. Again, whoever develops such standards first, where there may currently be voids, will have an advantage. System interoperability may be a keystone of capability integration early in the development process. As is the case in the training arena, new training software and simulators could benefit from efforts to enhance interoperability as early as possible (SPPS, 2022).

Finally, content may need to be purpose-built. No one will create a digital twin of the world in any reasonable amount of time; the process will likely be incremental. The decisions as to what content should be created and with what fidelity should be informed directly by initial purpose. Training provides an analogy for this concept, whereby virtual content should be mapped directly to training objectives and to targeted tasks and skills (Marler, 2022).

Risks and Threats in the New Domain

Current large-scale multinational exercises may provide an ideal mechanism of incremental development and testing of metaverses. Although these exercises are geared towards training (and international messaging of capabilities), they already leverage live, virtual, and constructive (LVC) capabilities for JADO (Marler et al., 2022). This involves linking real warfighters using real weapon systems with real warfighters operating virtual systems (e.g., a simulator) with computers controlling virtual systems (constructive).

As Marler et al (2023) detail in the context of homeland security, using metaverses may present a variety of risks and threats. Given that metaverses represent various forms of data (visual, written, aural, etc.), misinformation and disinformation will be risks as they are on the internet with social media (e.g., corrupting data in a common operating picture, modifying critical visual or text-based information). This may include multisensory deepfakes used to imitate leaders. Furthermore, much of the content might be ephemeral, like in-person conversations rather than permanent data.

Abuse and harassment may be another potential threat, even in the context of applications for military warfare. The internet has already seen various forms of abuse (Sum of Us, 2022). Furthermore, there are already reports of sexual abuse and harassment in current metaverses (Basu, 2021).

Finally, Marler et al (2023) note that “potential challenges with ethics and equity might be pervasive across many threats.” Even during early stages of development and use, priorities, values, and culture will have to be instilled and managed in virtual worlds as they should be in the real world. Military legal experts may need to be involved along with developers and users. Ultimately, even military metaverses may be used for social purposes, and this may enable various abuses or violations. Looking forward, as interoperability, accessibility, and fidelity increase, metaverses will gradually approach real-world environments, bringing with them comparable benefits and risks.

Related to ethical issues is the risk that decision-makers may become more detached from warfare and the consequences thereof. Metaverses that provide advanced COPs may remove leaders from first-hand engagements. In some sense, the real battle may become less real.

The Bigger Picture

In concept and practice, metaverses are not new. Many of the characteristics discussed in this paper are accessible and usable in some form, even today. This begs the question of what’s next? If organizations and states recognize the opportunity for a new warfare domain, if they somehow address all the noted challenges and risks, if they create the necessary content, then what?

A key avenue for advancement will be fidelity in all its forms (visual, physical, etc.). As fidelity improves, metaverses may approach perfect digital twins of the world, or at least parts of the world. The data requirements and implications of a complete virtual replica of even part of the world may dwarf those currently associated with AI. Advances in brain-computer interfaces may very well suggest the potential to merge real and virtual worlds amidst warfare (Binnendijk et al., 2019). As in Ender’s Game, the distinction between a simulation and a real, deadly battle may become mute. Then, the question is, what’s the difference?

References

BAE Systems, (n.d.). What is JADO? Available from: https://www.baesystems.com/en-us/definition/what-is-jado

Ball, M. (2021) Framework for the Metaverse. The Metaverse Primer. Available from: https://www.matthewball.co/all/forwardtothemetaverseprimer

Basu, T. (2021) The Metaverse Has a Groping Problem Already. MIT Technology Review. Available from: https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/12/16/1042516/the-metaverse-has-a-groping-problem/

Binnendijk, A., Marler, T., Bartels, E. M. (2019) Brain-Computer Interfaces: U.S. Tactical Military Applications and Implications. RAND Report RR-2996-RC. Available from: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2900/RR2996/RAND_RR2996.pdf

Card, O. S. (1977). Ender’s Game. New York: Tom Doherty Associates.

Chowdhury, S. and Marler, T. (2022) The Metaverse: What It Is and Is Not. Inside Sources.

Chowdhury, S. and Marler, T. (2024) Understanding and Measuring Hype Around Emergent Technologies. RAND Report PE-A3137-1. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA3137-1.html

CNET (2021) Everything Facebook Revealed About the Metaverse in 11 Minutes. CNET video. Available from: https://www.cnet.com/videos/watch-everything-zuckerberg-announced-at-facebook-connect-2021/

Kallenbron, Z. (2020) ‘In a Robot War, Kill the Humans’, Defense One. Available from: https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2020/08/robot-war-kill-humans/168038/

Kasubaski, B.C. (2019) Exploring the Foundation of Multi-Domain Operations. Small Wars Journal.

LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education (2020) Annex 3-1 Department of the Air Force Role in Joint All-Domain Operations (JADO).

Marler, T. (2022) Beware the Allure of Training Technology. Defense News. Available from: https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2022/05/18/beware-the-allure-of-training-technology/

Marler, T. (2023) Unlocking Training Technology for Multi-Domain Operations. The Air Power Journal. Available from: https://theairpowerjournal.com/unlocking-training-technology-for-multi-domain-operations/

Marler, R.T. et al. (2023) The Metaverse and Homeland Security: Opportunities and risks of persistent virtual environments. RAND Report PRJ-A2217. Available from https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA2217-2.html

Meta. (n.d.). What is the Metaverse? https://about.facebook.com/what-is-the-metaverse/

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Meta. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/meta

Park, S.-M. and Kim, Y.-G. (2022) A Metaverse: Taxonomy, components, applications, and open challenges. IEEE Access, 10, pp. 450–462

Poon, L. (2022) How Cities Are Using Digital Twins Like a SimCity for Policymakers. Bloomberg. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-04-05/digital-twins-mark-cities-first-foray-into-the-metaverse

Roach, J. (2021) Mesh for Microsoft Teams aims to make collaboration in the ‘metaverse’ personal and fun. Microsoft. Available from: https://news.microsoft.com/source/features/innovation/mesh-for-microsoft-teams/

Robinson, J. (2017) The sci-fi guru who predicted Google Earth explains Silicon Valley’s latest obsession. Vanity Fair. Available from: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/06/neal-stephenson-metaverse-snow-crash-silicon-valley-virtual-reality?srsltid=AfmBOoqd0BhGSkR3DnnL9Mg-0kYtHZRqXN93xKITTgwx-NnS7XnTTBoA

Roblox (2021). The Future of Communication in the Metaverse, September 2. Available from: https://blog.roblox.com/2021/09/future-communication-metaverse/

Scharre, P. (2018) Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War. W. W. Norton & Company.

Smart, J. et al. (2007) Metaverse Roadmap: Pathways to the 3D Web—A Cross-Industry Public Foresight Project. Metaverse Roadmap. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370132044_Metaverse_Roadmap_Overview_2007-2025_A_Cross-Industry_Public_Foresight_Project

Straus, S., et al. (2019) Collective Simulation-Based Training in the U.S. Army: User Interface Fidelity, Costs, and Training Effectiveness. RAND Report RR-2250-A. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2250.html

Sum of Us (2022) Metaverse: Another Cesspool of Toxic Content. Available from: https://www.eko.org/images/Metaverse_report_May_2022.pdf

U.S. Air Force (2020) Air Force Doctrine Note 1-20: USAF Role in Joint All-Domain Operations. Department of the Air Force.

U.S. Air Force (2020) Air Force Doctrine Publication 3-99: Department of the Air Force Role in Joint All-Domain Operations (JADO). Department of the Air Force.

United States Army (2018) The United States Army in Multi-Domain Operation 2028. TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1. Available from: https://adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-3-1.pdf